Citizen-Soldiers: Restructuring the Reserve Force and Capitalizing on Potential

The relationship between the Regular Force and the Reserve Force in Canada’s military structure is long overdue for reform.

The Regular Force is overstretched, understrength, and forced into roles it was never meant to fill. We've all seen the Regular Force routinely fighting wildfires, filling sandbags, and most recently deploying medics to Long Term Care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the Reserve Force has atrophied into a ghost of what it could be: underfunded, poorly equipped, and treated as an afterthought.

Canada is poised to rebuild it's military, finally. But we mustn't forget about the Reserve Force and what it was meant to be, and what it should be.

We need a Territorial Force. A modernized, professional, provincially directed version of today’s Primary Reserve. A force that handles domestic emergencies, provides regional security, and relieves the Regular Force of every role that distracts from its true purpose: warfighting.

Canada needs a military built around clarity of purpose: the Regular Force as the axe, and the Territorial Force as the toolkit.

A Brief History of the Reserve Force

Canada's military has long maintained a two-tier structure: a professional Regular Force and a part-time Reserve Force. This division was formalized in the aftermath of World War II, with the creation of a permanent standing army and a supplementary force of citizen-soldiers to be mobilized in times of national need. The concept echoes back to Canada's militia roots, where local units of volunteers defended their communities under provincial or colonial authority.

In 1968, the unification of Canada’s military under the Canadian Forces Reorganization Act brought all branches under a single umbrella—but the distinction between Regular and Reserve remained. The Reserve was meant to serve as both a strategic surge capacity and a link between the military and civilian society. Over time, however, it became increasingly marginalized.

It’s this model we now seek to reform and repair.

Remodelling the Citizen-Soldier

This proposal draws heavily from proven models abroad. The U.S. National Guard operates under state authority unless federally activated, handling everything from disaster response to civil security. Denmark’s Hjemmeværnet and Norway’s Heimevernet both use local, part-time forces to secure infrastructure, assist police, and patrol their territory. These are serious, respected units, not ceremonial uniforms.

Canada has the people, the history, and the geography to do the same. The Territorial Force would be:

- Provincially commanded, like the state-commanded U.S. National Guard

- Federally trained, to CAF standards

- Capable of declining deployments, unless formally activated by the Governor General

This keeps the Territorial Force grounded in the community—but tightly interoperable with the Regular Force when needed.

Why are we recommending the Reserve Force be Provincially commanded? Yes, this shift would represent a major structural change in how Canada manages domestic defence. Provincial command does not mean independence from federal oversight. It means that each province gains authority to shape, direct, and utilize its Territorial Force units for localized emergencies, disaster response, and civil assistance while remaining integrated under CAF standards for training and equipment.

Currently, when a province faces an emergency (flood, wildfire, or civil disruption) it must formally request assistance from the federal government, which then decides whether to deploy Regular Force assets. This causes delays and restricts rapid response.

Under the Territorial Force model, each province could call upon its own troops immediately, without needing Ottawa’s approval, and without charge. Units would answer directly to the provincial Lieutenant Governor in Council, ensuring responsiveness in times of crisis.

This shift also eliminates a significant financial barrier. Under the current system, provinces that request military assistance from the CAF may be billed for the cost of deploying troops and equipment. For example, during the 1998 Ice Storm that devastated Eastern Ontario and Quebec, military assistance was essential but had to be formally requested and could incur costs to the province. While the federal government often waives fees, the legal and bureaucratic hurdles remain in place.

With provincially commanded Territorial Force units, these costs are absorbed upfront through provincial budgeting, not retroactively billed. The provinces would own the capability, rather than rent it from Ottawa in a time of crisis. That’s not just faster, it’s fairer.

A perfect example of the current model’s failure was seen during the aforementioned COVID-19 pandemic. Regular Force medics were deployed into long-term care homes after civilian staff refused to work or quit en masse. This pulled essential personnel from military clinics and training centres, depleting the Regular Force's already strained medical capacity. It’s likely the provinces were billed for this deployment, at least in part. Had a properly equipped and structured Territorial medical component existed under provincial command, this response could have occurred faster, more appropriately, and without weakening the CAF’s own operational capability. This Regular Force deployment to provincial long term care homes cost taxpayers at least $53M according to various gov't sources.

Activation of the Reserve Force for federal or overseas operations would remain the purview of the Governor General, ensuring that these units are not turned into provincial militias, but rather remain constitutional elements of Canada’s national defence. Think of it as subsidiarity in uniform: national defence when necessary, regional response by default.

Real Training, Shared Infrastructure

Under this model, the Regular Force retains control of all training infrastructure—recruit courses, trades schools, officer development. This ensures the Territorial Force is trained to the same standard, maintaining a unified doctrine across Canada.

Territorial members who wish to serve full-time can take Class C–equivalent appointments, supporting both provincial and federal needs.

But the defining difference remains untouched:

Territorial Force members have the ability to respectfully decline.

They can decline deployments, decline training, decline exercises, decline relocation. They are not full-time soldiers. They are citizen-defenders. Regulars do not have this luxury.

Fixing the Employer Problem

One of the biggest barriers to Reserve participation has always been employer resistance—the fear of losing a worker to training or deployment with no compensation.

The Territorial Force solves this through:

- Provincial military leave legislation, guaranteeing job protection

- Employer tax credits or wage subsidies

- A “Service-Ready Employer” registry, promoting military-friendly hiring

- Preferential access to provincial public service jobs for Territorial members

Arm Them Like They Matter

When the Regular Force divests equipment, it should not be sold or scrapped, it should be downstreamed to the Territorial Force.

Imagine Territorial units training and deploying with:

- Leo 1s or legacy LAV IIIs

- Retired air defence systems

- Surplus bridging equipment and winter vehicles

This gear is more than enough for domestic operations. As one soldier succinctly put it:

“Yea, in a crisis, I’d rather ride into danger in an old LAV than in a f***ing green Chevy.”

Unit Highlights and Specialization Potential

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada (Toronto)

- Current strength: ~100–150

- Equipment: Light vehicles, C7 rifles, minimal modernization

- Proposed role: Urban warfare and public security in Toronto

The Black Watch (Montreal)

- Current strength: ~120–140

- Equipment: Light gear, no armoured vehicles

- Proposed role: Civil security, crowd control, and winter ops in Quebec

Governor General’s Horse Guards (Toronto)

- Current strength: ~100

- Equipment: C7s, soft-skinned G-Wagons; claim TAPV access

- Proposed role: Armoured reconnaissance and rapid deployment in Ontario

3rd Field Artillery Regiment (Saint John, NB)

- Current strength: under 100

- Equipment: C3 Howitzers (1950s design)

- Proposed role: Domestic artillery support, flood response, disaster area denial

- Note: Canada’s oldest military unit, predating most Regular Force formations

Many of these units are under-equipped, understrength, and underutilized. The Territorial Force model allows them to specialize by geography and threat profile:

- Urban units focus on riot control, critical infrastructure protection

- Rural units train in winter warfare, fieldcraft, and disaster logistics

- Coastal units integrate with port security and SAR efforts

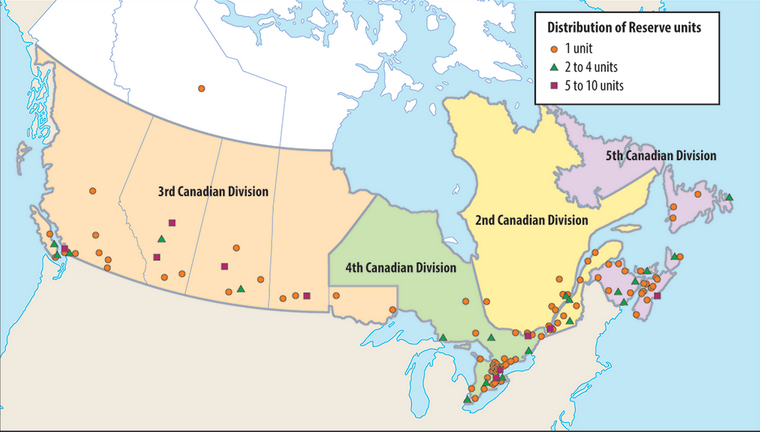

Right-Sizing the Territorial Force

Current Reserve units are often little more than skeleton crews. Most operate at a fraction of their historical or practical strength—sometimes with fewer than 100 personnel on the books.

To be functional and regionally relevant, each Territorial Force unit should aim for:

- Infantry units: 250–500 members depending on location

- Support or specialty units (e.g., artillery, cavalry, engineers): 150–300 members

- Rural detachments: Company-sized elements of 60–120 to maintain a local presence

For comparison:

- A properly staffed Regular Force infantry battalion should number 600–800 troops

- Unfortunately, current Regular battalions often fall below 400

Canada doesn’t need to mirror foreign doctrines but we must recognize that a Reserve unit of 90 soldiers is insufficient to handle even moderate domestic crises.

The Territorial Force must be scaled to the task and funded to sustain it. Not every unit need be a battalion but every community force should be something more than a token.

Air and Naval Reserve Reform

While the Army Reserve can evolve into the domestically focused Territorial Force, the Air Force and Naval Reserves require a different approach.

✈️ RCAF Reserve

- Composed mostly of former Regular Force personnel

- Primarily supports technical, logistics, medical, and intelligence roles

- No independent flying squadrons, serves as surge capacity

- Poor visibility and integration hamper effectiveness

Recommendation: Expand their domestic utility. Create specialist detachments for wildfire reconnaissance (e.g. drone teams), Arctic monitoring, and airfield support during disasters.

⚓ Naval Reserve

- Structured into Naval Reserve Divisions across major cities

- Provides trained sailors for augmenting Regular crews

- Contributes to port security, coastal ops, and maritime readiness

Recommendation: Expand domestic roles, such as coastal patrol, maritime SAR, and mine clearance. Introduce full-time reserve billets for leadership continuity.

These Reserve components should remain federally managed, but fully integrated with the new Territorial Force where possible. They serve as force multipliers, not provincial assets, but they must be made more relevant, better equipped, and clearly tasked.